History, theft and crime of the 30 million Breguet "Marie Antoinette watch"

Share

Breguet pocket watch no. 160 "Marie Antoinette"

Breguet pocket watch No. 160 "Marie Antoinette".

The Mona Lisa of the watch world or the Holy Grail of watchmaking

During her lifetime, the Queen of France, Marie Antoinette, placed great importance on surrounding herself with luxury. Her palace at Versailles was both admired and condemned nationwide for its enormous wealth. Her lack of concern for her suffering people and her lavish spending caused so much anger that in 1793 both Marie and her husband, King Louis, were executed by guillotine.

Although she was married, Marie's charm and beauty attracted several admirers, including the Swedish Count Hans Axel von Fersen (1755-1810) . Her admirer faced a dilemma: How do you impress a woman who already has everything in looks, wealth, and power? The Count's response was to commission watchmaker Abraham-Louis Breguet to create a timepiece that, in his own words, would be "...as spectacular as possible." Breguet, already a purveyor to the court at the time, had carte blanche, with no time or financial constraints.

Unfortunately, the Queen never saw her watch No. 160, called "Marie-Antoinette," as it was not completed until 1827 , 34 years after her death, four years after the passing of A.-L. Breguet, and 44 years after it was commissioned. During Breguet's exile in Switzerland, work was suspended for about seven years (1789–1795). A large part of the creation of this watch was Michael Weber's work.

Breguet's workshop records that Weber worked 725 hours on this clock over the next three years, starting in 1812 , and was paid 7,250 francs. Other watchmakers, such as Charles Oudin , Etienne Tavernier , Augustin Merceron , and Lallemand, also participated in the creation of this clock.

Antoine-Louis Breguet was responsible for its final completion in 1827. According to the company's archives, the production cost was 17,070 francs, far more than any other Breguet watch produced at that time.

By comparison, another early perpetual calendar pocket watch, the famous No. 92, created for the Duc de Preslin, sold for 4,800 francs. Antoine-Louis retired from watchmaking in 1833 and was succeeded by his son , Louis Clément Breguet .

The Breguet No. 160 pocket watch had a diameter of 63 mm and a perpetual calendar with day of the week, date and month, equation of time, striking mechanism with repeating minutes, quarters and hours, independent second hand, jumping hour indicator, power reserve indicator and thermometer.

It was a "perpetual" movement, meaning it featured an automatic mechanism equipped with an oscillating solid platinum oscillating weight. It also featured Breguet's invention, the "pare-chute" shock protection .

Even by today's standards, it was an astronomically expensive piece. The most precious materials (including gold, platinum, rubies, and sapphires) were used without any time or cost restrictions. The watch is encased in gold and has a transparent dial that reveals the intricate mechanics and turning gears within.

Breguet used sapphire stones in the mechanism to reduce friction. The watch came with an original enamel dial, which was replaced with a transparent one. However, the original enamel dial was retained.

The "Marie-Antoinette" remained in the possession of Breguet et fils until it was sold to the Marquis de la Groye de Provins, who returned it for repair in 1838 but never returned after the repairs. His identity, however, is unclear, as it is not possible to find a corresponding profile in the genealogy of the Marquisate de la Groye.

It is possible that the name in the archives of Breguet, who returned the watch to Breguet for repair in 1838, was misspelled, a not so unusual fact.

It may have been Edmond Eugène Philippe Hercule de la Croix, Marquis and second Duke of Castries (1787-1866), who at that time was commander of the "Chaussers" Corps of the French Imperial Army stationed in Provins: the Marquis de la Groye (a misspelling of de la Croix) de Provins. He was the grandson of the Minister of the Navy and Marshal of France Charles Eugène Gabriel de la Croix de Castries (1727-1801), who had purchased the watch.

The "Marie-Antoinette" is also said to have been exhibited at the Great Exhibition of 1855. The "Marie Antoinette" remained in the family's possession until 1887 , when it was sold by Eugénie Caroline Lassieur (1815-1889), the widow of Louis Clément Breguet, to Sir Spencer Brunton for £600.

After the death of Sir Spencer Brunton in 1901, the watch was purchased by Murray Marks (1840-1918), a well-known Dutch art dealer and collector, who sold it in 1904 to Louis Albert Desoutter (1858-1930) . Desoutter was an English watchmaker of French origin and a well-known Breguet watch expert.

Desoutter then sold the watch for the last time to Sir David Lionel Salomons (1851-1925) , a British scientific author and lawyer, to expand his extensive watch collection, which already included over 100 Breguets. He wrote several books on Breguet watches and published a catalog of his collection.

Upon his death in 1925 , Salomons left 57 of his finest Breguet pieces, including No. 160 "Marie-Antoinette," to his daughter Vera Bryce (1888–1969) . His widow inherited the rest of the collection. She then auctioned the watches at Christie's in London in 1964/1965 .

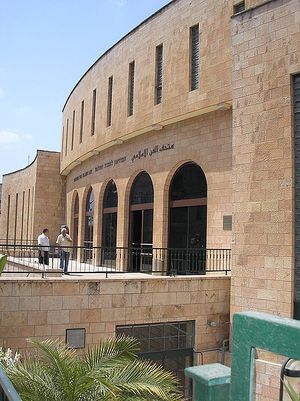

After World War I, Vera moved to Jerusalem and became an active philanthropist. After the death of her professor, Leo Aryeh Mayer, rector of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, she founded the L.A. Mayer Institute for Islamic Art and donated her valuable clocks to the museum for display in a dedicated gallery.

The LA Mayer Institute of Islamic Art opened to the public in 1974 , after Vera had already died.

Theft with far-reaching consequences

On the evening of April 15 , 1983 , Israeli thief Na'aman Diller, aware that the alarm system of the LA Mayer Institute of Islamic Art had temporarily failed due to a breakdown, planned one of the most famous thefts in Israeli history.

The exceptional collection of Breguet watches donated by Vera Bryce Salomons, including the "Marie Antoinette," was housed in a glass case at the rear of the building.

Thanks to his slender build, Diller was able to slip into the museum. He stole 106 watches along with some paintings, aware that the stolen watches were too famous to be sold on the open market. He stored most of the items in safe deposit boxes in Europe and the USA and then settled in Los Angeles.

Police had considered Diller a possible suspect since 1983, but found no evidence. Checking auction houses and contacting collectors worldwide proved ineffective. Apparently, the "Marie Antoinette" and the other precious timepieces had disappeared.

The loss of the Marie Antoinette clock was a severe blow to both French culture and watch lovers around the world.

A perfect copy

In 2004 , with the theft still unsolved after more than 20 years and no one knowing what really happened to the original "Marie Antoinette", Nicolas Hayek , founder of the Swatch Group and new owner of Breguet Montres SA , asked his watchmakers to build an exact replica of this masterpiece of watchmaking.

Recreating such a complicated watch using only old documents was a real challenge for the company's technicians and watchmakers. The original technical drawings in the Breguet Museum archives, along with a few other images and descriptions, provided the only available information and guidance on the watch's functions and styling details.

After four long years of research and reconstruction, the new "Marie-Antoinette" watch with the number 1160 was presented to the public by Nicolas Hayek at Baselworld 2008 .

A sensational return

In 2006, the LA Mayer Institute of Islamic Art was contacted by a Tel Aviv lawyer, Hila Efron-Gabai, and informed that one of her clients owned some valuable timepieces, the existence of which had been revealed by her husband "on his deathbed."

While battling cancer, the man confessed to her that he had stolen these items from the museum two decades earlier. The woman lived in the United States and wanted to return them to their rightful owner.

Nevertheless, she asked to remain anonymous and receive some money in return, as there was a reward of $2,000,000 for anyone who could help solve the case.

Through negotiations, the price was reduced to $35,000. Fifty-three of the 106 stolen watches were back in the museum's hands in August 2007. For several months, the museum concealed the discovery and kept the watches hidden.

But the secret soon became known, and police investigations led to the discovery of a document from the warehouse where the stolen watches were kept, bearing the name of a woman living in Los Angeles, Nili Shamrat. It was easy for the Israeli police to determine that Nili Shamrat was the widow of Na'aman Diller.

After their marriage in 2003 , the couple traveled to Tel Aviv to store the stolen timepieces in a safe. A year later, Na'aman Diller died of cancer. At 6:00 a.m. in May 2008 , police officers knocked on the door of an unassuming house in Tarzana, California, with a search warrant.

After searching the residence of Nili Shamrat, a Hebrew teacher at Shalhevet High School (a parochial school in Los Angeles), officers found watches, Islamic artifacts, and oil paintings, many of which had been stolen from the LA Mayer Museum of Islamic Art in Jerusalem about 25 years earlier, Nili Shamrat was arrested in 2008.

After questioning Shamrat for three days, police began to solve a decades-old mystery about the theft of Queen Marie Antoinette's No. 160 watch. In the following months, police discovered 43 more stolen watches in two bank safes in France.

After 25 years, a total of 96 of the 106 timepieces stolen by Na'aman Diller were returned to the LA Mayer Institute for Islamic Art. The case was finally solved. In 2013, the watch was valued at $30 million.

Source: WatchWiki