Sammler-Uhren

Junghans Zeppelin airship clock, Imperial Air Force, World War I

Junghans Zeppelin airship clock, Imperial Air Force, World War I

Couldn't load pickup availability

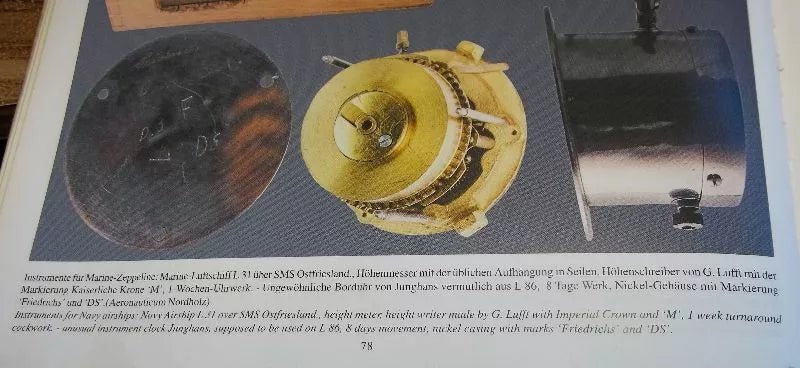

The wonderfully rare piece in this offer corresponds essentially to the one from LZ 86 described by the "military watch pope" Konrad Knirim, except that the rare example in this offer has to be opened to wind it up and Knirim's had a winding mechanism located outside the case.

Today we can no longer tell from this unique and super-rare piece of military watch history which naval airship it served on, but there is not the slightest doubt about its originality and authenticity, see Konrad Knirim page 78ff

During the entire airship era up to the Hindenburg disaster, there were exactly 130 Zeppelins in the Imperial Air Force and later the Reich Air Force -

In total, there were exactly 130 airships with this model of the original on-board clock of the Imperial Navy Zeppelins, developed by Junghans specifically for Zeppelins, and many of them were burned on enemy missions or lost during the respective shootdowns and crashes.

A more exclusive highlight of any military watch collection is hardly conceivable than one of definitely a maximum of 300 pieces ever built and used worldwide

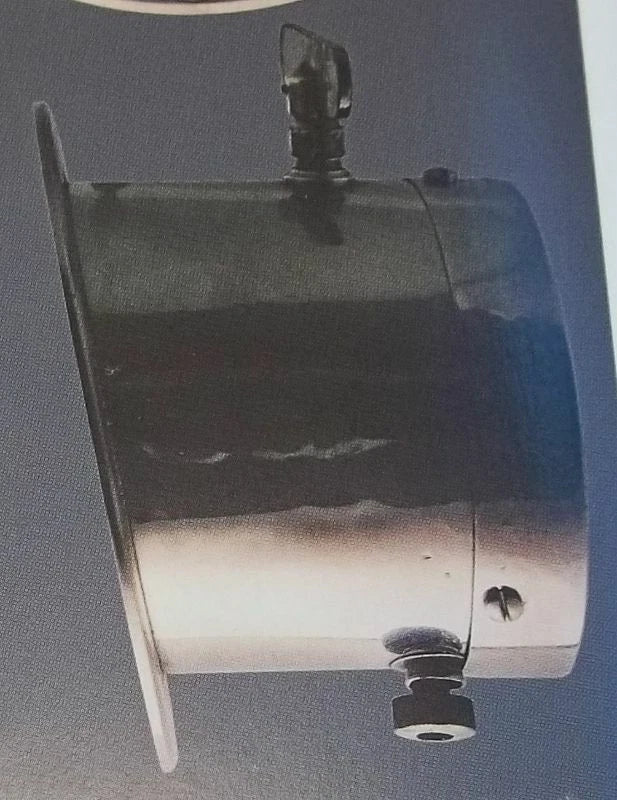

Case diameter: 75mm, case height 105mm, flawless, unrestored porcelain dial with hairline cracks, but restored and stable, Junghans signed with Roman numerals, blued steel hands in Breguet style

Blued Breguet-style hands - just like the LZ86 model shown by Konrad Knirim, solid, concave, presumably original mineral crystal, held in place by a triple-screwed metal ring/bezel

The entire onboard clock is slightly angled, which clearly identifies it as a Zeppelin instrument clock. The instrument lacks a metal/brass case back, as it was mounted on a presumably wooden dashboard. The lower edge of the case has various holes for mounting, some of which have been torn open and soldered/repaired.

Condition: Good condition for its age. The presumably original mineral crystal is sturdy and scratch-free with slight chipping on the edge. The bezel rings are in good condition, with no dents or cracks. This magnificent piece was completely serviced in 2006 and has only been wound very rarely since then, making it technically in top condition.

Winds smoothly, runs and functions perfectly (accuracy not tested - when opened, this magnificent piece of (military) watch history is wound from the back with the large, recognizable wheel and adjusted with the very small one above, good condition, dial restored, stable and completely preserved with minor hairline cracks

Best technical and good optical condition, dial unrestored with the mentioned hairline cracks, brass case well preserved, adjusting screws and shafts top

Good collector's condition: EZ 2 - considering the age and origin, normal, visible signs of wear, runs smoothly (accuracy not tested), all bezel screws present and easy to grip

Information on the use and end of military airships/Zeppelins in the Imperial Air Force of World War I:

The first and the last of the proud giants of the sky:

Prototype LZ 1

The prototype, LZ 1 (LZ for "Luftschiff Zeppelin"), was 128 m long, 11.65 m in diameter, and powered by two Daimler engines, each producing 10.4 kW (14.2 hp). To balance ( trim ) the approximately 13-ton structure, a 130 kg weight was used, which could be moved between the front and rear nacelles. 11,300 cubic meters of hydrogen provided lift as a lifting gas , but the payload was only about 300 kg.

On July 2, 1900, at 8:03 p.m., the airship's first ascent took place in Manzell Bay, watched by approximately 12,000 spectators along the lakeshore and on boats. The flight lasted only 18 minutes before the winch for the counterweight broke, and LZ 1 was forced to make an emergency landing on the water. After repairs, the technology showed some potential in two further ascents over the following weeks, notably beating the speed record of 6 m/s (21.6 km/h ) previously held by the French airship "La France" by 3 m/s (10.8 km/h). However, it was still unable to convince potential investors . With the financial resources exhausted, Count von Zeppelin was forced to dismantle the prototype, sell the remains and all the tools, and dissolve the company.

Building LZ 129

On March 4, 1936, the new Zeppelin LZ 129 "Hindenburg" (named after former Reich President Paul von Hindenburg ) was finally completed and undertook its first test flight. Previously, there had been speculation that LZ 129 would be named "Hitler" or "Deutschland," but Hitler insisted that nothing bear his name that could be at risk of being destroyed in an accident or catastrophe, which could thus be considered an ominous omen. In addition to its propaganda flights, the "Hindenburg" soon began supporting the "Graf Zeppelin" on transatlantic routes.

In the new political situation, Eckener was unable to obtain the helium needed for the filling, as the USA, which remains the only country that extracts it from natural gas in significant quantities, had since imposed an embargo . So, after careful consideration, the "Hindenburg" was filled with hydrogen again, like its predecessors, not least for economic reasons. Aside from the significantly lower procurement price of the gas, passenger capacity increased from 50 (helium) to 72 (hydrogen). The propulsion system was powered by diesel engines for the first time at Zeppelin.

The end of the LZ 129

On May 6, 1937, the tail of LZ 129 caught fire during landing in Lakehurst, and within seconds, the world's largest airship was engulfed in flames. The exact cause of the Hindenburg disaster initially remained unclear. Although there was frequent speculation about a possible act of sabotage (by the Nazis or their opponents), both old and new findings clearly support an accident scenario in which the Zeppelin's innovative paint played a fatal role. Subsequently, the hull caught fire due to electrostatic discharge, eventually igniting the hydrogen as well.

Hugo Eckener's theory of the Hindenburg disaster assumes that the sharp turn caused a guy wire inside the zeppelin to snap, damaging a hydrogen cell. The hydrogen escaping upwards from the rear of the airship ignited due to static electricity caused by a second thunderstorm front over Lakehurst and the lowering of the ropes to the ground crew, grounding the zeppelin.

A similar theory suggests that the hydrogen escaping upwards was not ignited by static electricity, but rather by sparks from an engine's power cable.

Either way, the Lakehurst disaster marked the end of German airship travel. Confidence in its safety was permanently destroyed, and further passenger transport in hydrogen-fueled zeppelins was out of the question from then on. LZ 127 "Graf Zeppelin" was decommissioned one month after the accident and converted into a museum .

Only test drives with LZ 130

Hugo Eckener continued to try to source helium from the USA for the Hindenburg's sister ship, the LZ 130 "Graf Zeppelin II," but to no avail. Intended as the new flagship of the Zeppelins, the airship was completed in 1938 and, again filled with hydrogen, undertook a few workshop and test runs, but never carried passengers. Another project, intended to surpass even the Hindenburg and the Graf Zeppelin II in size, the LZ 131 , never progressed beyond the production of a few frame rings.